Exploring Western Architecture:

Richard Neutra

The architectural styles of Western Europe and North America have evolved over centuries of cross-pollination of cultural progeny, each generation of architect reliant on the former for cues as to its bearings, for better or for worse, stretching back millennia. The Modernist movement in architecture had within its ranks a superfluity of talented iconoclasts whom revised architectural history to suit the ideology of the bold new Modern designers of Europe, such as: Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Walter Gropius, to name a few. Western architects of the 1920’s and 30’s saw a boon in their proliferation of this new style of modular construction, that promoted no ornament, and destined the style to environments across the world, provoking the title ‘International Style’ (see Figure 1). By doing so, this style of architecture transcended regional pigeonholing and embraced the vast disparities between regional terrains, clients, national values, and civic identities.

When we look into the architecture of the U.S.A. through the lens of the Modern and International movements during the 1920’s through to present day, few architects project an understanding of these design principles as well as Richard Neutra. While he may not be the inventor of Modernism in architecture, he “made it respectable and prestigious” (12 Lavin). Neutra is an originator of environmental design and regionalist architecture, whereby his Californian homes have become emblematic of the American International Style, most notably for their breathtaking vistas, responsible ecology, client personalization, deconstructing the barriers between the interior and exterior, and Modernists principles.

Richard Joseph Neutra was born in Vienna, Austria on April 8th, 1892 and immigrated to Chicago, U.S.A. in 1923 at the age of 31. He was educated in Vienna after serving in the First World War graduating from the Technische Hochschule in 1917. Previously to his military post in the Balkans, he came under the influence of architect Adolf Loos which whom he took many philosophical cues from (9 McCoy). Neutra’s career took him on many paths, including as an employee for a landscape gardener in Switzerland, a municipal worker in Brandenburg Germany aiding in the resettling of industrial workers in the post-war environment, and as a draftsman and collaborator in the office of expressionist architect Eric Mendelsohn. As a young man, Neutra was deeply moved by the works of Otto Wagner, especially his subway stations, in which he “delighted in running up and down the wide steps… enchanted with the unexpected view of the Danube caught through openings in the walls” (8 McCoy). The coming Second World War encouraged Neutra to look for a new home, whereby America beckoned him to seek her raw material, pristine landscapes, and, to Neutra, architects of near deity status: Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright.

Neutra befriended Sullivan towards the end of his life, and consequently met Wright at Sullivan’s funeral and became a draftsman of his. At Taliesin, Neutra made and impression drawing the project known as “Sugar Loaf” (see Appendix 1), an unrealized spiral form motor hotel and a precursor to Wright’s monumental New York landmark, the Guggenheim Museum (12 McCoy). While visiting Taliesin, Neutra worked for Chicago’s Holabird and Roche as draftsman number 216, where he helped design an office that was to be his education in the methods in which big buildings were organized and constructed (12 McCoy). It was not until 1925 that Neutra opened his own practice when he moved to Los Angeles. He maintained his practice called Richard Neutra, Architects and Associates, successfully with a steady roster of clients from 1925, eventually partnering with his son Dion (at which time the firm’s name changes to Richard and Dion Neutra, Architects and Associates) until his death on April 16th, 1970, at age 78. The firm is still actively taking commissions.

Neutra’s practice began with a creative flourish that saw new building techniques in reinforced concrete, steel substructures that meant large span for glazed openings, and expanded application of glazing as a substantial architectural feature. His Jardinette Apartments at 5128 Marathon St., Los Angeles, built in 1927 was the first building in Los Angeles in the International Style and executed using reinforced concrete construction. The five-storied residential building’s ‘contemporary’ look held fast to the codes that Modernism operated by, a look that was to evolve into Californian Modern, a uniquely south western Modern sub-genre. Neutra designed the components of the Apartments as slabs of reinforced concrete cantilevered so to project out over each ascending storey, held up by a traditional post and beam system (Art and Culture). With generous spans of reinforced steel, Neutra was able to install strip windows that made corners seem to float, while covered balconies were a feature for the individual residences. His flat roof design incorporated gardens, a motif that we are to see throughout his index of projects. Neutra wanted integral organic systems to be in symbiosis with the functions and therefore forms the vast majority of his buildings.

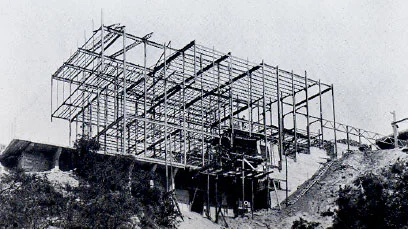

Various projects affirmed Neutra’s obvious respect for

engineered systems and the technology that made them practical, but none did

more to make him famous than the Lovell Health House built in Los Angeles,

circa 1928.

Its steel assembly was fabricated into components and transplanted from the factory to the property and assembled in less than two man-days (14 McCoy). Jackson writes that the house “cost $65,000 and would have cost 20 percent more had Neutra not been his own contractor” (24). Many claim that it is the first house in America whose entire frame is made with steel and is an “apotheosis of the International Style” (13 Lavin). Its massing is comprised of super-human sized slabs that seem to defy gravity as they perch atop near invisible runs of glazing punctuated by spindly darker coloured mullions that are decorative rather than structural, as though tracery on gothic cathedrals done by Piet Mondrian. The Health House became well known in both the U.S.A. and Europe, causing Drexler to proclaim that “(i)n Europe by 1929 neither Gropius nor Breuer nor Mendelsohn had built houses of comparable sophistication”

An interior view shows large windows, recalling Gothic Cathedral’s vast spans of glass (Becker).

This image of the all-steel construction of Neutra’s Lovell Health House became an icon of the revolutionary building techniques now available to architects (39 Drexler, Hines)

Mondrian’s Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue. He was highly influential to Modern Art (Write Design Online)

The Perkins House, in Pasadena, CA, 1955, shows Neutra using an amorphic pond that transgresses interior and exterior (41 Lavin).

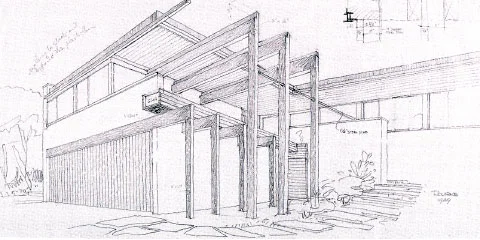

Neutra’s work from then on would remain famous for its technological innovations. Characterized now by his use of large glass panes that, in effect, made most walls to the exterior practically invisible, Neutra sought to diminish the barrier between the interior and exterior, incorporating vistas and inviting nature inside. Pools of water, either as a component of a greater garden, swimming pool, or reflecting pool, comprise another major component used time and again in Neutra’s work as both a motif and as practical insulation (see Figure 10). A hallmark of a his houses are large centralized laminated wood beams that project out from the core massing of the house and connect to a post that protrudes from the ground¸ both appear turned so that the wider side of the construction dominate the intersecting horizontal and vertical lines. Neutra named these features “spider-leg outrigging” (63 Lavin) and they appeared either in rhythmically repeating groups, or as the dominant horizontal member of the structure. It was his pioneering in the sphere of prefabricated homes that caused him to be regarded as a “technological wizard” (14 McCoy) and raised the American International Style to an elevated level of respect across the globe.

Neutra’s characteristic “spider-leg outrigging” that appeared often in his structures and helped embellishes the geometry of his buildings (63 Lavin).

The Singleton House, LA, CA, 1960, shows a single spider-leg outrigger that was common in Neutra’s work (84 Spade).

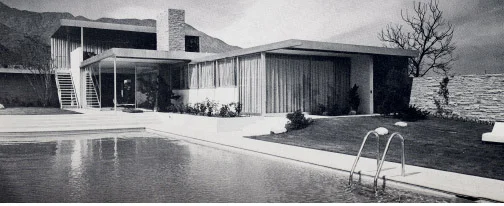

This famous photograph of Neutra’s Kaufmann House gives the impression that calm prevails here, and one can escape the hustle and bustle of the city while at home (Desert Utopia).

The Kaufman House, constructed in Palm Springs in 1946, is the most extraordinary of Neutra’s desert homes, as it is an oasis within a harsh desert environment, whose glittering blue swimming pool, almost cavernous eaves, and pavilion scale, delight the viewer with a Modernist gem amidst sandstorms and merciless terrain. Its pinwheel plan (see Appendix 2 – 100 Drexler, Hines) separates the important areas into wings, of which only two are visible at one time from the ground (see Appendix 2).

What grabs me most about the Kaufmann House is its simplicity. Sliding glass walls recall Japanese paper screens that can open a plan up from end to end if one so desired (see Figure 13). First glances mask the complex and involved design process that this prefabricated package must have

A poolside view shows drawn curtains being used midday to reflect solar radiation away from the house’s interior (103 Drexler, Hines).

necessitated. The House is an essay on the triumph of technology over handmade homes, whose thesis successfully argues for a modular design that both conquer its environment while merging with it delightfully. Neutra rescinds the detrimental effects and conventional notions of desert living by assimilating the desert’s effect. By using stone floors and masonry central pillar, he utilizes stone’s slow latent energy capacity so to provide an interior source of warmth when temperatures plummet at night. Moreover, a glass envelope allows solar radiation to enter the dwelling warming surfaces. Light coloured curtains reflect the same radiation during peak temperatures (see Figure 14). The orientation, material choice, and temperature control predict planning techniques of what has since come to be called environmental design.

The Eagle Rock Club House (a.k.a. The Eagle Rock Recreational Center) served its community as a hub of physical and artistic activities, as well as public assemblies. Neutra’s modular wall system allowed the building to accommodate multiple uses (Neutra.org).

Neutra enjoyed a prolific career designing commercial buildings inside and out, as well as institutional buildings such as the Corona Avenue School (1935), The California Military Academy (1936), the Kester Avenue Elementary School (1951), The Orange Coast College (1957), and The Lincoln Memorial at Gettysburg (1963), to name a scant few (see Appendix 3).

The plan of the Eagle Rock Club House is mostly an open one, aside from administrative offices and utility closets. Note the beautifully laid out landscape design (97 McCoy).

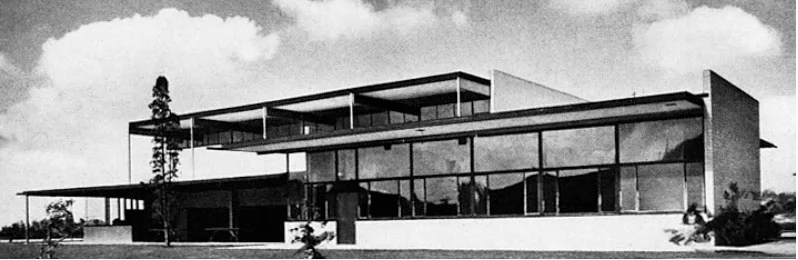

None from these classifications of buildings, in my estimation, seems more realized than the Eagle Rock Club House built in Los Angeles in 1953 (see Figure 15). Neutra termed public and commercial spaces simply as “Humans in Groups” (22 McCoy), so to distinguish a once both its usage and occupants. The Eagle Rock Club served these ‘humans in groups’ much in the way we think of current day community centres, accommodating a gymnasium, dance floor, theatre, and assembly hall, by expanding and contracting the interior by way of proprietary lift-up walls (see Figure 16). The building itself is breathtaking in its horizontal emphasis and uninterrupted vista of the Californian mountains, visible beyond expertly landscaped grounds and through an ostensibly invisible exterior enclosure. Roof planes appear weightless as he cantilevered steel substructure project deeply past their expected capability (see Figure 18), as Neutra took full advantage of steel’s capacity for bearing a building’s forces. (A. Morassutti '02)

The sweeping vistas that Neutra designed at Eagle Rock make one feel as though they are outside, despite being safely out of the harsh California elements (97 McCoy).

It is ironic to think of Neutra as a devotee to a style named for its international adaptability, given how regionally exclusive his works seem to be. The reliably searing Californian climate, however, is particularly suited to the type of buildings Neutra designed well for. His environmental design philosophy is tuned in such a way that he places architecture directly across nature’s path, so that its materials and systems may absorb, reflect, entrap, or simply allow energy to pass through (see Figure 19). In effect, the architecture of Neutra took on the characteristics of a living organism, such as breathing and requiring a core temperature, so that the organisms living within its skin could do so comfortably.

The view along the east front of the Eagle Rock Club House shows a roof slab that appears to be supported by inadequate posts, when really the cantilevered steel roof system carries the load of the roof (96 McCoy).

This residence in Silverlake, CA (name and date unknown), displays most of the elements which made Neutra’s homes so famous and, in turn, him to become perhaps the most prolific residential designer in America, non-residential buildings notwithstanding. Here we see the pool reflecting the architecture whose glass is reflecting the environment surrounding it. The reflecting pool seems to connect with the Silverlake reservoir creating the illusion of unending space (23 Neutra).

Appendices

Appendix 1: When Neutra went to work at Taliesin for Frank Lloyd Wright, he produced these drawings for the Motocar Observatory, on Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland, in 1924 (35 Drexler, Hines).

Appendix 2: A site plan view of the Kaufmann House, in Palm Springs, CA, built circa 1946. Note the pinwheel layout of the house, where “wings” of the house seem to be repeated along the rotational axis of the dining room (100 Drexler, Hines).

Appendix 2 con’t: The Kaufman house has a pyramidal stacking design, whereby the one storey residence is capped with a sitting area that is open on three sides, perched atop the rest of the house. A lovely place to relax out of the sun (101 Drexler, Hines).

Appendix 3: The California Military Academy, CA, 1936, Seems ahead of its time regarding its vast square footage to house and train military personnel. Neutra was in his mid-forties when he designed this building (Artnet).

Appendix 3 con’t: The Kester Elementary School is an institutional building type that still contains many of Neutra’s trademarks, such as the horizontal emphasis of the overall design, the cavernous eaves, and delicate mullions that appear to support the overhead mass of the roof (Loureiro, Amorim).

Appendix 3 con’t: The Orange Coast College: Robert B. Moore Theatres is an example of Neutra using the circle or curves to achieve a particular effect. My guess would be that this auditorium on campus was given this shape to aid the acoustics of an assembly or performance (Orange Coast College).

Appendix 3 con’t: Neutra’s Lincoln Memorial in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, is one of the few buildings he did outside of California. The building is unique in that he uses circular geometry to embellish Lincoln’s address, which is carved on the interior of the rotunda, also known as a ‘Cyclorama’ (World Monuments Watch).

Works Consulted

About: Architecture. “Great Buildings: Lovell House”. April 1st, 2007. http://architecture.about.com/library/bllovell-neutra.htm.

Archiweb. “Richard Josef Neutra”. March 27th, 2007. http://www.archiweb.cz /architects.php?type=arch&place=&action=show&id=132.

Art and Culture. “Richard Neutra”. April 1st, 2007. http://www.artandculture.com/cgi-bin/WebObjects/ACLive.woa/wa/artist?id=57.

Art Net. “Richard Joseph Neutra”. April 1st, 2007. http://www.artnet.de /Artists/LotDetailPage.aspx?lot_id=DC358050780CD258.

Becker, Gerhard. “Online Kunst.: Computergarten April”. April 1st, 2007. http://www.onlinekunst.de/april/08_Neutra_Richard_Josef.htm.

Desert Utopia. “Gallery: The Kaufman House: Richard Neutra, 1947”. April 1st, 2007. http://www.desertutopia.com/g1.html.

Drexler, Arthur and Hines, Thomas S.. The Architecture of Richard Neutra: From International Style to California Modern. New York, USA: The Museum of Modern Art. 1982.

Eircom. “Winkins Architecture”(?). April 1st, 2007. http://homepage.eircom.net/~winkens/img-wink/neutra.jpg.

Geoanalyzer Britannia. “Savoye House”. April 01, 2007. http://geoanalyzer

http://geoanalyzer.britannica.com/eb/art-6078.

Jackson, Neil. The Modern Steel House. London, England: Taylor and Francis. 1996.

Lavin, Sylvia. Form Follows Libido. Massachusetts, USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2004.

Loureiro, Claudia and Amorim, Luiz. “Vitruvius: Por uma arquitetura social: a influência de Richard Neutra em prédios escolares no Brasil”. March 27th, 2007. http://www.vitruvius.com.br/arquitextos/arq020/arq020_03.asp.

McCoy, Esther.richard neutra. New York, USA: George Brazillier Inc. 1960.

Neutra, Dion. Richard Neutra: Building with Nature. New York, USA: Universe Books. 1971.

Neutra.org. “Neutra: 75th Birthday”. April 02, 2007. http://www.neutra.org

/birthday_remarks.html.

Orange Coast College. “Visual and Performing Arts: Robert B. Moore Theatre”. April 2nd, 2007. http://www.orangecoastcollege.edu/academics/divisions/visual_arts/.

Spade, Rupert. Richard Neutra. London, England: Thames and Hudson. 1971.

University of Washington. “Jardinette Apartments”. March 29th, 2007. http://www.washington.edu/ark2/archtm/USA81.html.

University of Virginia. “Richard Neutra: Lovell House”. March 27th, 2007. http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA01/Lisle/30home/modern/lovell.html.

World Monuments Watch. “100 Most Endangered Sites: 2006: Cyclorama Center”. April 04, 2007. http://wmf.org/resources/sitepages/united_states_cyclorama_center.html.

Write Design Online. “Color Design Rules”. March 27th, 2007. http://www.writedesignonline.com/resources/design/rules/color.html.